Leadership

models illuminate areas for personal growth and development using various

lenses to focus on different blind-spots.

My personal journey in leadership has progressed with fits and starts,

finally gaining momentum as I moved into residency as I developed a personal

vision of how I could and would lead.

I’ve discovered new skills, styles and situations to be a more

thoughtful and deliberative leader. Through

anecdotes from residency, I will share my current progress. Firstly, I will show my Situational Leadership in the clinic. Secondly, I will show how my Leadership style has keenly sharpened

under fire in a national organization. Finally, I will discuss how Authentic Leadership has affected me.

Tackling New Leadership Situations in a

Family Medicine Clinic and Residency

Our clinic has

small teams for coordinating care with patient outreach. We have weekly

meetings to review our tasks like calling patients to come in for routine appointments,

developing cancer screening scripts/protocols and other routine tasks. As

an intern, I discovered that leading a medical team on rounds in the wards does

not work the same way as a multidisciplinary setting with a secretary, medical

assistant and nurse. For example, when I

started working with “Jay,” a front-desk staff member, I needed to titrate my

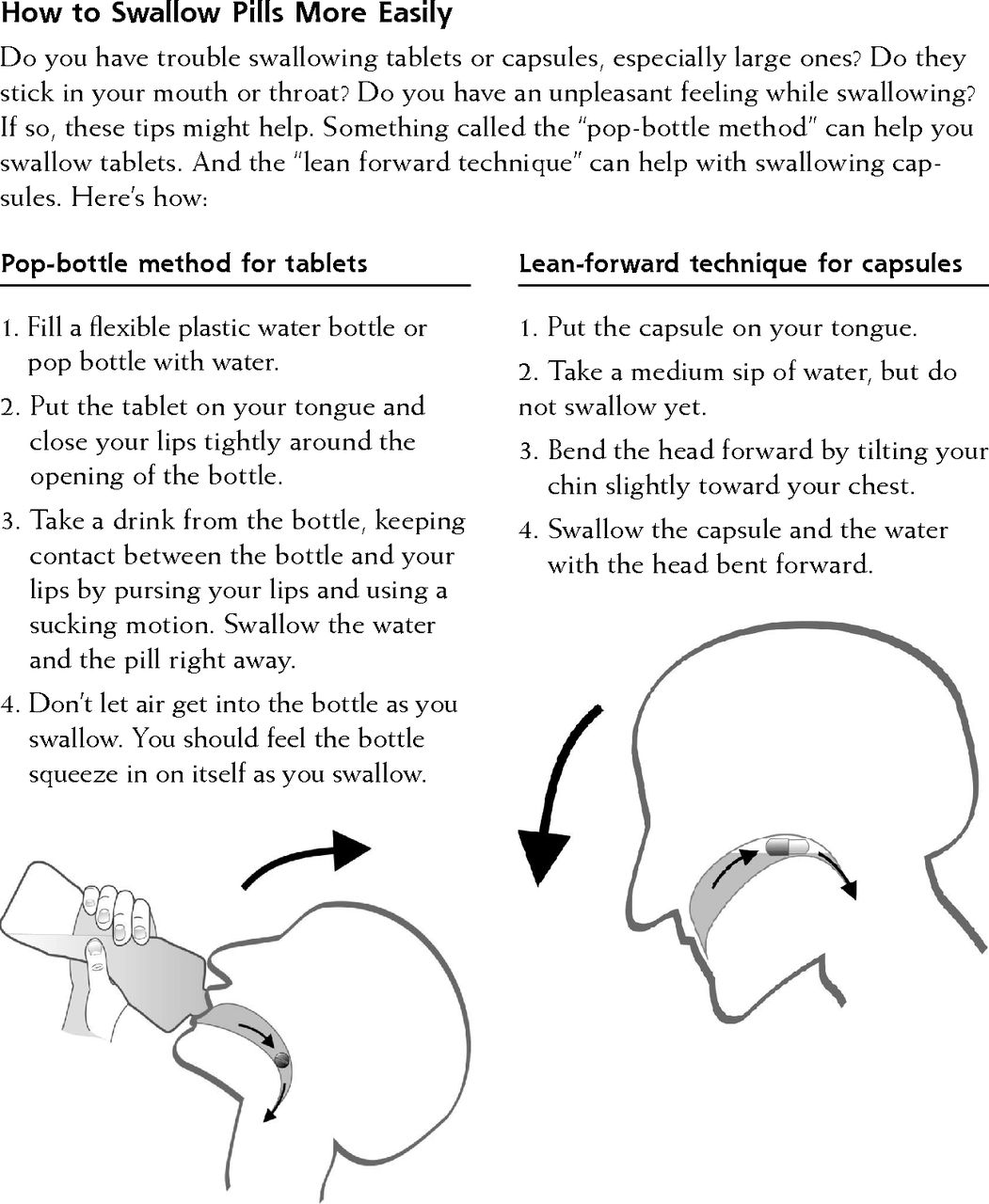

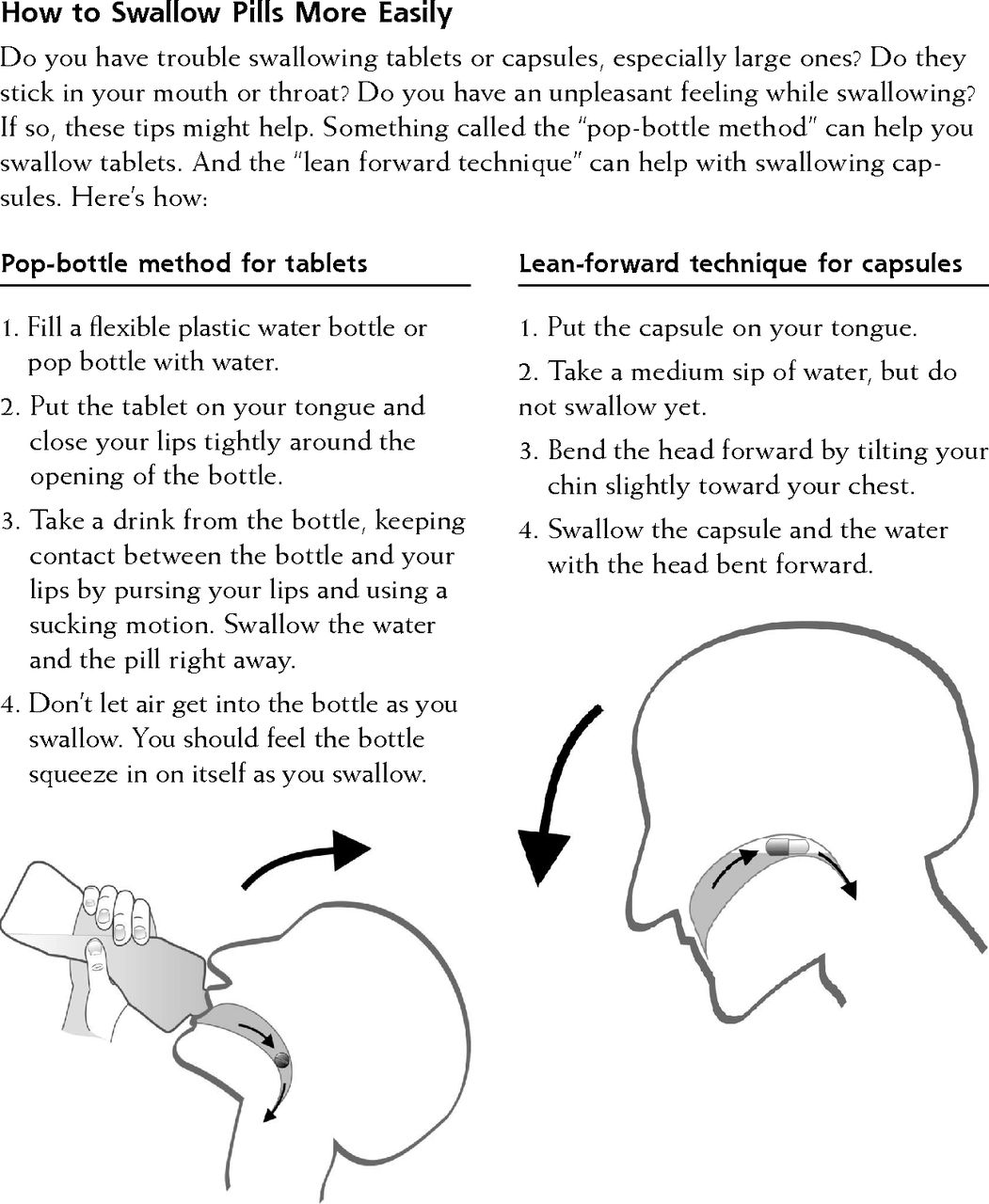

leadership downward to suit his level of development. Following Hersey and Blanchard’s (1969) Situational Leadership II (SLII) model

of supportive and directive behaviors, I started with a hands-off approach. (Appendix 1)

Initially I used supportive “participating” behavior: High-relational,

low-task behavior. I gave “Jay” control

of day-to-day decisions while I was available to facilitate problem

solving. I sent messages along with some

tips on how to manage the work through the day.

However, the work was not completed at the end of the week, so I switched

to a coaching “selling” style: high-relational and high-task behavior. I

asked another front desk secretary to sit down and coach his outreach to give him

tips on how to complete the tasks in a timely fashion.

After a month went by, I sat down and used a directive “telling” style:

low-relational, high-task behavior. I gave

him direct tasks and directly supervised him carefully. Only under this level of scrutiny did I discover

that his inbox was cluttered with multiple versions of my messages I kept

sending to him that he was afraid to touch or act upon them without direct

approval.

My initial

problem was not matching “Jay” with his appropriate development level. Directive and supportive behavior needs to

match with the development level of the follower on a competence/commitment

continuum. I had initially assumed that “Jay”

was a D3 employee with moderate/high competence, when in fact he was a D1-2

employee with low competence. However, he

does not have the associated "high commitment" level. In order to work with him effectively, I need

to help motivate him.

When I

recognized the utility of the SLII model , I investigated Hersey and Natemeyer’s Power Perception Profile (1979) to assess

what my preferences were for a utilization of various power bases and identify

which type of maturity or development level best suited my preferences. There is a spectrum of power bases necessary

to influence people's behavior at specific levels of maturity: from

coercive-connection to reward-legitimate to referent-information and finally,

expert. (Appendix 2) My highest scoring preferences were in the

highest level domains of Expert and Information. According to Hersey and Natemeyer, this

correlates with a high maturity follower and I work best with M3-M4

followers. “Jay” is an M1 follower so a

better method of approaching his situation would be to form strong connections

with influential/important people in the front desk and provide small

observable rewards for those who do well.

A criticism I have with this model is that it implies that low maturity

followers respond best to “sticks rather than carrots” and it encourages a

coercive power base over a reward power base in some situations. While this may hold true in some fields like

the military, I do not think that harsh discipline has positive effects in the

healthcare field except to drive people away and hurt relationships. Finding this leadership model lacking in some

respects, I sought out other ways I could work better with a team.

Developing a New Leadership Style in the Committee of Interns and Residents

In

residency, I signed up as a union representative and quickly rose through the

ranks from regional delegate to hospital chapter president to state executive

board member for the national organization. During my fellowship, I have

worked as an elected resident board member on the Committee of Interns and

Residents (CIR), a U.S. national union organization for resident-physicians. Connecting with other future leaders, having

discussions about our collective residency mission/vision/values and developing

national programming around these issues has been exciting and stimulating for

me. However, it took me two years to

become the authentic leader we needed.

Initially I

had a laissez-faire leadership style with a hands-off attitude. During our monthly phone calls, I would mute myself

and tune out while doing other work. I

was disengaged in the tasks and had only superficial relations with the other

board members and senior CIR staff. I

was inexperienced and untrained in leadership. I did not engage in an ongoing dialogue

between the resident delegates. I showed

poor governance; I neglected to help develop policies for success and I did not

monitor for policy compliance/adherence. I engaged in what Blake and Mouton would term “Impoverished

Management (1,1)” with “little

contact with followers and could be described as indifferent, noncommittal,

resigned, and apathetic.” (Blake

and Mouton 1985, Appendix 3)

However, at

the end of my first year, we had an internal leadership crisis – the staff

executive director was up for a 5-year term contract renewal and we found out

that about half of the senior staff was dissatisfied with his management. There were an unprecedented number of union

negotiations ongoing in addition to new chapters being recruited while record

amounts of chapter losses also took place.

As a result CIR suffered low staff morale, divisive internal conflicts,

and a high attrition of key staff members through both resignations and

firings. I found myself face-to-face

with the sinking realization that I was a poor leader in a situation where

strong governance in a period of stress and change was critical. A series of

emergency meetings by the board was called.

A key quote made by the ex-president has stuck with me.

“We have been absentee landlords,

holding the power and influence but letting our local staffers run the

organization.”

In the past

year, I changed from an “Impoverished

(1,1)” toward a “Teamwork (9,9)” leadership style with high concern for

results and people. (Blake and Mouton

1985, Appendix 3) In order to do so, I

considered the personal frames of Expert and Informational power, my areas of

strength. I applied these personal frames toward

knowledge development and relationship-building to better engage in concerns on

results and people. I became an expert

on the subject of leadership through the Dundee course and used this competence

to solidify a strong corporate mission, vision, values statement and five year

strategic plan. Energizing fellow

resident board members, I developed strong relationships despite a growing

division between two sides of the board and we were able to agree on core parts

of a leadership development plan for our executive director.

Here is a key passage from an email exchange

during the discussion process that illuminates how I drew connections between

steps of our strategic plan development, using George’s Authentic Leadership principles of “True North” (2007) and

Collins’ and Porris’ “Big Hairy

Audacious Goals” (1996)

"A compass, I learned

when I was surveying, it'll... it'll point you True North from where you're

standing, but it's got no advice about the swamps and deserts and chasms that

you'll encounter along the way. If in pursuit of your destination, you plunge

ahead, heedless of obstacles, and achieve nothing more than to sink in a

swamp... What's the use of knowing True North?" – Abraham Lincoln

Imagine that CIR is taking

a physical journey towards a destination.

We are the leaders of this group through the wilderness of

residency. We are the ones with vision

and direction. We are providing

guidance.

Where do we want to go in

the next 3-5 years?

We can walk towards a hospital and rally a group of dissatisfied

residents, we can walk to a town hall and support legislation, we can go to a

conference or class room and learn about something we aren't getting in our

residency, etc. … Some paths may lead us

down dead-ends or take us on a long, expensive tangent. Others may be shortcuts that attract new

members or engage our current members to participate more in the journey.

Why are we walking down

some paths and not others?

I feel that this is because deep down; we know what we want at

the end of residency. We know why we

went into medicine. And we are looking

for ways to help our patients, to help our fellow residents and to pave the

path and make it safer and higher-quality.

These are the core values.

We are aiming towards the “Big,

Hairy and Audacious" True North.

Each step should take us a little closer. Each activity we have should reflect a value …

that provides the driving motivation to keep us walking.

(abridged email, full exchange in attached

leadership portfolio)

As George’s

interviews with great leaders showed, Authentic

Leadership is about something more than traits alone: “[the] team was startled to see that you do not have to be born with

specific characteristics or traits of a leader.

Leadership emerges from your life story.”(George 2007) This reflective exercise shows a few examples

from my life story in residency and fellowship.

The

components of Authentic Leadership model are self-awareness, internalized moral

perspective “true north,” balanced processing and relational transparency. (Appendix 4)

Reflecting on this model raised my awareness that developing Authentic

Leadership meant two things for me.

1) My relationship with “Jay” has struggled due to my “false front” and

lack of transparency with my feelings. I

have been passive-aggressive in my leader-member interactions and I will strive

to be more open without coming across as abrasive or aggressive.

2) Initially in CIR, I contributed to a culture of disengagement. In a period of critical change, I recognized

how I was complicit and at fault. I

helped shift the CIR executive board from a management organizing/staffing

discussions toward a leadership paradigm with vision-boarding and

coalition-building.

Moving

forward in future leadership positions, I will be open and aware of my own

personal failings. I will center myself

around my internal moral compass. I will

become even-keeled and measured in my emotions, thoughts, and actions. I will develop deeper bonds with my team to

find out what drives us all so we can pump each other up when we are down. I will be an Authentic Leader.

Appendix 1:

Situational Leadership

Appendix 2:

Power Perception Profile

1. Coercive power is derived from having the

capacity to penalize or punish others. (French and Raven 1962)

2. Connection power is based on connections with

influential or important people… in which compliance occurs because they try to

gain favor or avoid disfavor of the powerful connection. (Hersey, Blanchard and Natemeyer 1979)

3. Reward power is derived from having the

capacity to provide rewards to others. (French and Raven 1962)

4. Legitimate power is associated with having

status or formal job authority. (French and Raven 1962)

5. Referent power is based on followers’

identification and liking for the leader. (French and Raven 1962)

6. Information power is based on the ability of

an agent of influence to bring about change through the resource of

information. (Raven and Kruglanski 1975).

7. Expert power is based on followers’

perceptions of the leader’s competence. (French and Raven 1962)

Appendix 3: Leadership Style Grid

Appendix 4: Authentic Leadership

Bibliography

Blake, R.

R., & Mouton, J. S. (1985) The

managerial grid III. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company.

Collins, J.

and Porras, J. (1996) Building Your Company’s Vision. Harvard Business Review.

George, B.

(2007) Discovering Your Authentic Leadership.

Harvard Business Review. Reprint

R0702H.

Hersey, P.

and Natemeyer, W.E. (1979) Power

Perception Profile -- Perception of Self. Center for Leadership Studies.

University Associates, Inc.

Hersey, P.,

Blanchard, K. and Natemeyer, W.E. (1979)

Situational Leadership, Perception, and the Impact of Power. Group

Organization Management. 4(4) p418-428

McCaffery,

P. (2010) The Higher Education Manager's

Handbook. Second Ed. New York: Routledge.

Raven, B.

& Kruglanski, W. (1975) Conflict and power. In P. G. Swingle

(Ed.), The structure of conflict. New York: Academic Press